At the grocery store, blueberries come in a box. But months before that, they started out

on a bush, a bush that needed soil, water, fertilizer and finally, the help of a tiny insect --

that industrious pollinator, the honey bee.

In 2017, nearly 2.7 million honey bee colonies pollinated more than twenty kinds of

crops across the 50 states. If that wasn’t enough, in 2016 honey bees produced 162

million pounds of honey, a staggering amount when considering a single female worker

bee makes less than a teaspoon in her lifespan.

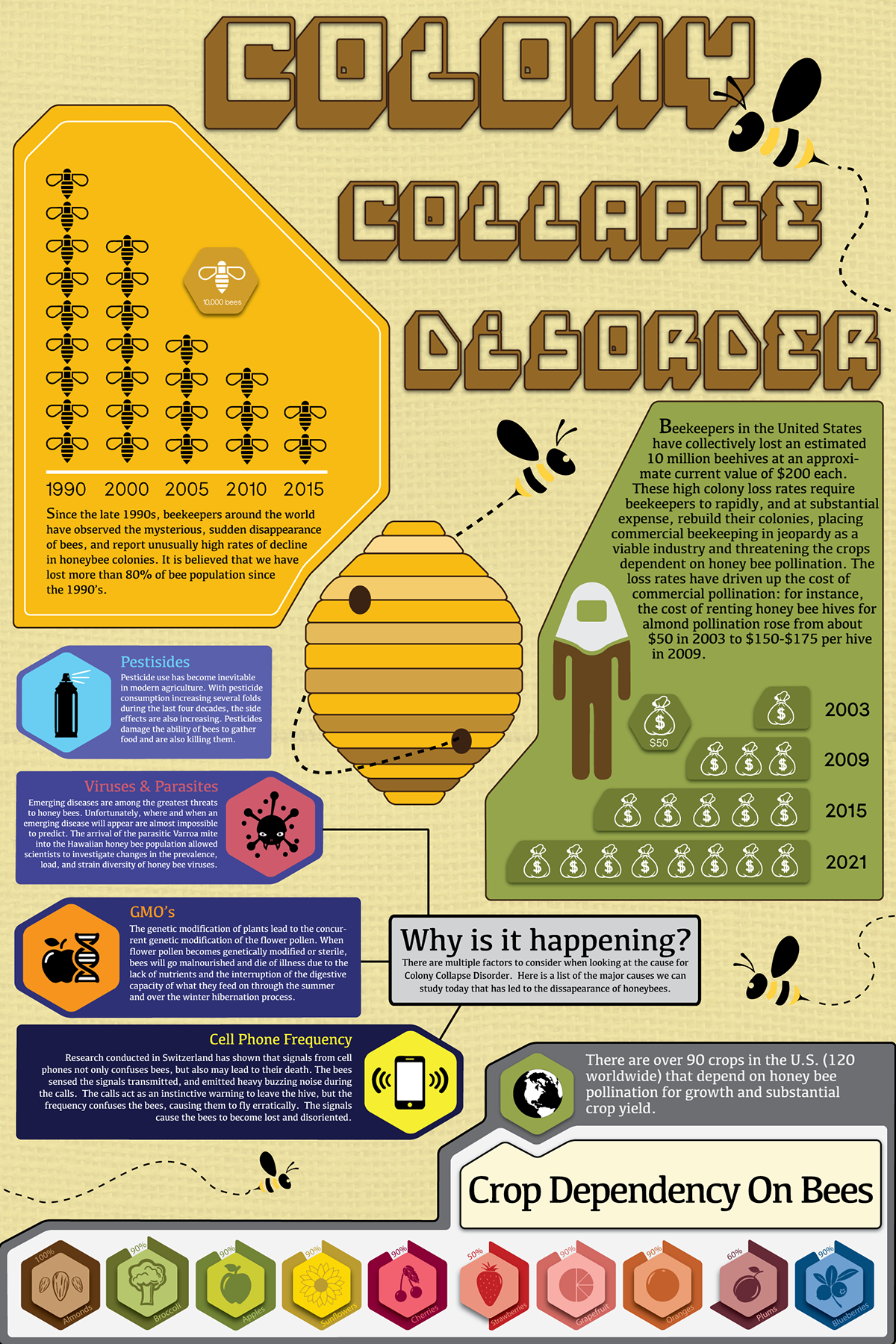

Unfortunately, the length of that life span may be growing shorter. Between March 2016

and April 2017, the average U.S. beekeeper lost 33 percent of their honey bee colonies,

according to the Bee Informed Partnership, a non-profit run by beekeepers, scientists

and epidemiologists. At peak population, as many as 80,000 bees make up a colony.

David Tarpy, a North Carolina State University entomology professor who specializes in

honey bee biology, said the high mortality rate of the country’s honey bees can be

attributed to the confounding effects of pesticides, poor nutrition, loss of genetic

diversity and in particular, the parasitic varroa mite. The tiny mites, less than 1.5mm

long, suck blood, shorten the lifespans and cause mutations in their hosts.

“Varroa mites are kind of public enemy number one,” Tarpy said.

The mites can do even more damage when colonies are weakened by pesticides. In

2006, scientists began researching how neonicotinoids, a class of insecticides used

around the world, may negatively impact bees ability to forage for food. Bees are more

susceptible to pesticides if they are poorly fed -- bees not only need a sufficient supply

of nectar, which is put at risk by habitat change, but a diverse diet, which can be difficult

as more farms turn towards monoculture.

The final issue, of genetic difficulties, occurs when beekeepers grow new hives from old

ones. To combat bee losses, beekeepers will split a healthy colony into multiple hives,

establishing new queens who can lay up to 3,000 eggs a day. Without careful selection

during this process, genetic traits that promote healthy and productive bees can

become rarer.

Losing bees has always been a part of the beekeepers’ world, especially when

wintertime hits hungry colonies. But for the last 10 years, winter colony losses have

been higher than beekeepers deem acceptable, the BIP survey reported.

“It’s harder to keep bees now than it used to be,” said Randall Austin, a 13-year

beekeeper and member of the Orange County Beekeepers Association.

Bee reports that document the reduction from 6 million colonies in the 1950s, when

every family farm had a hive, to the 2.7 million colonies modern large-scale

agribusinesses move around on flat-bed trucks may seem to show an out-of control

decline in honey bees. But because beekeepers can manage their populations, the

honey bee won’t go extinct. That fact doesn’t make the larger die-offs easier for their

Keepers.

“Losing your hives is like losing a part of your family,” said Leigh-Kathryn

Bonner, the owner of Bee Downtown.

Bonner’s “bees-ness,” as the company calls it, is one of the many organizations in the

Triangle working to promote honey bee health. Bee Downtown maintains hives for

businesses and corporations in urban areas like downtown Durham, keeping bee

populations thriving in urban areas.

The OCBA also promotes bee health by running a 10-week bee school to teach good

colony management practices, which keep disease and parasites like the varroa mite

from spreading.

“I want my neighbors to know what they’re doing,” said Austin, who works with the

school. “If they don’t, their problems can spread to my bees.”

Tarpy hopes that research on genetic diversity will also help to make bee colonies better

able to survive the parasite and pesticide threats. Tarpy is involved in NC State’s Queen

and Disease Clinic, which tests reproductive quality and health of beekeepers’ queens.

Genets will be a component of reducing varroa mite stress, but not a cure-all, Tarpy

Said.

“Dealing somehow with varroa is really critical,” he said. “Increased habitat is another

way, to make sure bees are not nutritionally stressed.”